“One of the most scheming women that anyone could imagine.”

This article was originally published in The (Macon) Telegraph.

by Amy Condra

Anjette Lyles’ influence still lingers in this lush Southern town. Beneath the pink blossoms of cherry trees and in the shadows of stately homes that escaped the wrath of Sherman, lurks a seamy tale of superstition and murder.

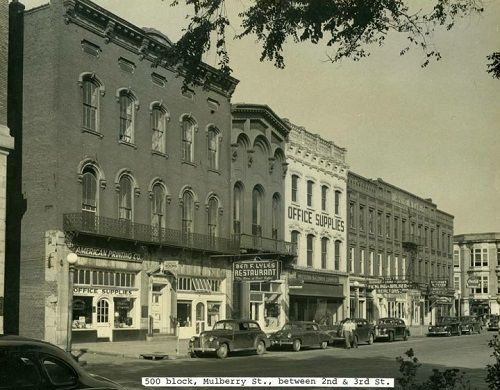

In the 1950’s, Anjette presided over a café she named “Anjette’s Restaurant.” Amidst the clattering of silverware and the soft murmur of conversation, she served prominent businessmen, politicians and attorneys — a crowd she dubbed the “brass hats of Macon.”

When her own charms weren’t enough to win this modern entrepreneur what — or whom — she coveted, Anjette turned to an old tradition of roots, candles and spells. Yet, as her ambitions grew, these methods were slow to deliver.

Finally, she resorted to arsenic.

Her horrifying schemes began to unravel on October 8, 1958, first in a courtroom in Macon, then across the front pages of The Telegraph and through the gossip told by people who still, almost 30 years later, can’t help but listen when they hear the name,“Anjette Lyles.”

“Foul Play Suspected”

On April 4, 1958, Anjette’s nine-year-old daughter, Marcia Elaine Lyles, died. The cause of her death was initially unknown.

Ten days prior to her passing, Marcia’s physician had voiced concerns about her symptoms. He asked Dr. L.H. Campbell, Bibb County medical examiner, to examine his young patient. Campbell thought that a rare organism in Marcia’s lungs was to blame, and, shortly after the child was declared dead, an autopsy was performed to confirm this diagnosis.

Then the coroner showed Dr. Campbell three anonymous letters that had been sent to Marcia’s great-aunts in Cochran, and subsequently, secretly, shared with him. One chilling message stood out: “Please come at once. She’s getting the same dose as the others.”

This revelation prompted a second, more thorough, autopsy. Samples of Marcia’s liver, kidneys and hair were preserved in fruit jars. These, along with two bottles of Terro ant poison, were sent to the state crime lab in Atlanta

“Anjette Donovan Lyles, the 32-Year-Old Murder Suspect”

Investigators began to wonder if the child’s mother, Anjette Donovan Lyles, might be responsible. Harry L. Harris, an assistant chief investigator for the Bibb County Sheriff’s Department, led the inquiry into Marcia’s mysterious death.

“No one wanted to believe she did it,” Harris told The Telegraph, 25 years after Marcia’s death. “No one suspected her. Macon was then a sleepy town. Everybody knew everybody.”

And everybody especially knew Anjette Lyles. She owned and operated Anjette’s Restaurant on Mulberry Street, a popular gathering place for those who enjoyed both the food and the outgoing friendliness of the woman who served it.

No one imagined that, behind the cheerful smile and warm hugs, was a woman who had methodically planned and carried out the murders of four members of her family.

On April 25, the bodies of Anjette’s first husband, Ben Lyles, Jr., and mother-in-law, Julia Young Lyles, were disinterred. Traces of arsenic were found in both of them. Arsenic was also found in the body of Lyle’s second husband, Joe Neal Gabbert.

And, arsenic was found in Marcia’s body.

On May 6, Anjette Lyles was arrested for murdering her daughter. The other indictments against her were left pending.

“’Voodoo’ Material is Found in Lyles Home…”

Bill Tribble’s reporting brought Anjette’s secret spells into public view: “A weird assortment of bottles and vials, which Sheriff James I. Wood termed ‘voodoo equipment’ has been discovered in the home of Mrs. Anjette Donovan Lyles,” reported Bill Tribble. Among these items were several small containers labeled Egyptian Love Powder incense, Sweet Spirit of Nitre and Adam and Eve root in oil, along with a tall glass vial containing wax from a burned black candle.

Witnesses claimed that they had also seen green and red candles burning in Anjette’s restaurant and kitchen. Such candles were believed to signify good luck in money and love.

More ominously, three empty bottles of arsenic-based ant poison were found in Lyles’ kitchen cabinet.

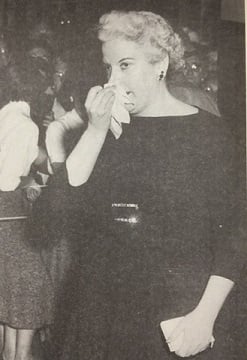

“Widow Unmoved by Staring Crowd”

The trial, which began on October 8, attracted huge crowds to the Bibb County courthouse, as spectators jostled for a glimpse of Anjette.

Blythe McKay captured the scene for The Telegraph: “During a morning recess an official told those behind the ropes that there were a few more places in the courtroom, and unfastened the rope. Women dashed toward the door and so did one man, an elderly crippled man had been limping around the hall on a cane. He tilted the cane over his shoulder and scooted.”

Macon’s fascination with the case extended to Anjette’s fashion during the proceedings. Many paragraphs of news coverage were dedicated to detailed accounts of Anjette’s clothes and hairstyles: “Hair style changed—her white hair, which she wore at that time in a ponytail and shoulder-length page boy, had also been cut into a shorter feather-type hair style. She wore shell-pink nail polish and a small wrist watch.”

One newspaper story analyzed both the accused’s black dress, with rhinestone buckle and matching earrings, and her “almost statue-like” stoicism as the prosecuting attorney, Charles F. Adams, called her “one of the most scheming women that anyone could imagine.”

“Testimony About Marcia: Tears Fall at Anjette Trial”

Spectators paid close attention to the parade of witnesses who testified against Anjette.

A nurse recalled that, although fruit juice was available at the hospital, Anjette insisted on bringing her own juice, saying, “she meant for (Marcia) to drink it.” The nurse said the girl would then become violently ill.

Tribble, reporting for The Telegraph, noted that Anjette’s maid, Carmen Howard, testified she had found a bottle of Terro ant poison in a black bag belonging to her employer.

Carmen recounted, “Mrs. Lyles squeezed a lemon into a glass, added water to it and carried it into the restroom along with the black bag… she then drove Mrs. Lyles to Parkview Hospital and left her. About three days after Marcia was admitted to the hospital she began to telephone her everyday… she said the child sounded cheerful. After Mrs. Lyles took the glass of lemonade to the hospital, the Howard woman said, she never again received a telephone call from Marcia.”

Although Marcia was initially admitted for an acute respiratory infection, she soon developed severe symptoms, including a high fever and a bluish rash, and her kidneys temporarily stopped functioning.

Charged With “Hate and Greed”

Investigators believed that Anjette methodically poisoned four members of her family by stirring Terro, which contained arsenic, into drinks — including lemonade, buttermilk and coffee — she would then offer to her victims.

Prosecutors sought a motive for the murders. After her arrest, Anjette told criminal investigators she hadn’t benefited from any of her relatives’ deaths.

However, she later admitted she had received a total of $48, 750 from insurance policies, benefits and inheritances.

She had used some of this money to purchase a car, according to a Macon used car dealer. He testified that he took Anjette and her new boyfriend, Bob Franks — who had been her second husband’s boss — to a dealership where she traded in a 1955 Oldsmobile for a new Cadillac. She wrote a check for $2,538 to make up the difference between the two vehicles.

In an unsworn statement to the court, Anjette maintained her innocence. She claimed that she loved her child and hadn’t killed her.

“Sentenced to Die for Murder of Nine-Year-Old Daughter”

The week-long trial concluded on October 15. Anjette Lyles was convicted of murdering Marcia and was sentenced to die by electrocution.

However, in the 1950s, Macon was still segregated and not yet in step with the Civil Rights era to come. A white woman being executed in the electric chair was, at that time, an unpopular political proposition.

A sanity commission was appointed to examine Anjette, and subsequently, declared here to be a chronic paranoid schizophrenic. Governor Ernest Vandiver had her committed to a state hospital for the criminally insane. She would live out the rest of her days in Central State Hospital in Milledgeville.

Anjette Lyles died of natural causes in 1977. She is buried near her first husband, and her daughter Marcia, in a family plot in Wadley, Georgia.

The story of Anjette Lyles continues to fascinate audiences. She has been immortalized in Jaclyn Weldon White’s book “Whisper to the Black Candle,” and in Denver Pickard’s play, “The Shadow Behind the Flame”