All stories and photographs on this page were created by Amy Condra during her visits to Nepal and Rwanda with the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID).

Sagarmatha WORTH Group, Banke District, Nepal

The Janaki Rural Municipality is located in far-western Nepal, where agriculture plays a significant role in the economy.

Here, a group of women have joined together to form a savings and loan group, called the Sagarmatha WORTH Group. “Sagarmatha,” a Nepali term meaning “head of the sky,” is not only the official name for Mount Everest, the highest peak on Earth — it also symbolizes the lofty ambitions of this group.

Each woman gives a mandatory savings contribution of about 25 cents per week. As the group’s savings increase, members can start taking out loans to start or expand small businesses.

Women in this group have opened shops, provided sewing services and raised livestock such as pigs, goats, buffalo and chickens. Members have also saved for projects such as home construction, continuing education and the establishment of an emergency fund.

One woman invested her savings in her poultry business. She started with 60 chickens, and recently added 50 more. She also borrowed money from the group to build a chicken coop, and, having recently repaid that loan, she plans to borrow additional funds so she can fill her new coop with more chickens.

“I started saving little by little, and that became easier and easier,” she said. “Now, it is a habit!”

The extra money she has both saved and earned by growing her business has helped support her family. Like many women in the group, she uses her business’ income to ensure that her children can receive an education.

“Before, girls were not attending school,” said Nilam Singh, “but now we send them.” And, she says, with extra income generated through group activities, more families can afford to send their daughters to secondary school after they have completed their primary education.

This savings and loan group follows the WORTH model, which is a micro-banking program designed to help women lift themselves out of poverty. WORTH groups work to not only improve women’s economic prospects, but also their political participation. Members are encouraged to take literacy training, and learn about local governance and planning. Many women, such as Singh, go on to become activists and leaders in their communities.

Singh became interested in public service after completing a leadership training program. She also started participating in social campaigns, particularly those related to gender-based violence. Singh says that other women began encouraging her to run for public office, and she was elected to be a representative in her local ward.

Along with other members of the group, Nilam has worked to promote social development in their community. “We have pushed for road construction, and drainage and irrigation projects,” she said.

Members of the savings group say that, together, they will continue to advance their economic and political futures.

“It can be hard for women to stand up, to be independent,” said one WORTH member. “Women need each other for support. We stand for each other.”

Kaule Drinking Water Project, Surkhet District, Nepal

In the mountains of Nepal’s Surkhet District live a small group of women from the Badi community. For years, these women spent much of their days fetching water. The walk to a drinking water source could take up to three hours and, once there, women would wait in long lines to fill jugs they would then have to haul back home.

Knowing their efforts and resources could be better spent, these women, led by Chairwoman Pawitra Oli, initiated the Kaule Drinking Water Project. Before they could implement the project, though, the Badi women faced a challenging hurdle: the reluctance of the local government to provide support.

Oli went to the Sahare Village Development Committee three times to ask for assistance. Government officials did not believe the Badi women would be able to pull off such an ambitious project, and brushed aside their request. Oli persevered until, finally, she was able to persuade the government to help.

The community established an all-women Drinking Water User Group committee, which built a drinking water system featuring three public taps. The system, which included an underground tank, was built with the assistance of a local NGO. Each of the village’s 27 households contributed about 50 cents per month for maintenance.

Government officials were so impressed by the project’s success that they praised the women in an appreciation letter to the village, began inviting them to village development committee meetings, and hold them up as an example for others in the District.

For an impoverished community where many people feel compelled to leave their country in search of employment, a crucial benefit of the drinking water project has been the economic growth opportunities it creates.

“We have saved 3-4 hours per day,” said Pawitra Oli. “This has given us time to focus on other work.”

That other work can generate much-needed income for families in the community. One woman was able to obtain a two-month construction job based on her efforts on the water project. With this extra money, she was able to upgrade her home.

Now that the water has come, other needed improvements in the community have followed — such as schooling for the village children. For years local children had not been going to school, due to their parents’ fears they would be teased for seeming poor or unkempt. But the confidence the Badi women gained from their well-received achievement made a difference: now, parents are proudly sending all the village’s children to school.

However, the women of the village knew that, for their community to fully thrive, they also needed electricity.

“Other kids study in light,” said Motisara Pun, a member of the village. “Our homes don’t get light, so our kids don’t get to study.”

The women, who now feel empowered to voice their requests, decided to lobby the local government for a village electrification project. Once again, their efforts paid off. Villagers secured $4800 in government funds to connect their homes to the main electrical grid. The community also received $8000 to build a small road to connect the village to the main thoroughfare.

These infrastructure projects not only enhance the village’s standard of life; they also provide time and resources for further income-generating activities and improvements.

“Before we had no water for drinking,” said one woman in the village. “Now we have water — and now we have hope.”

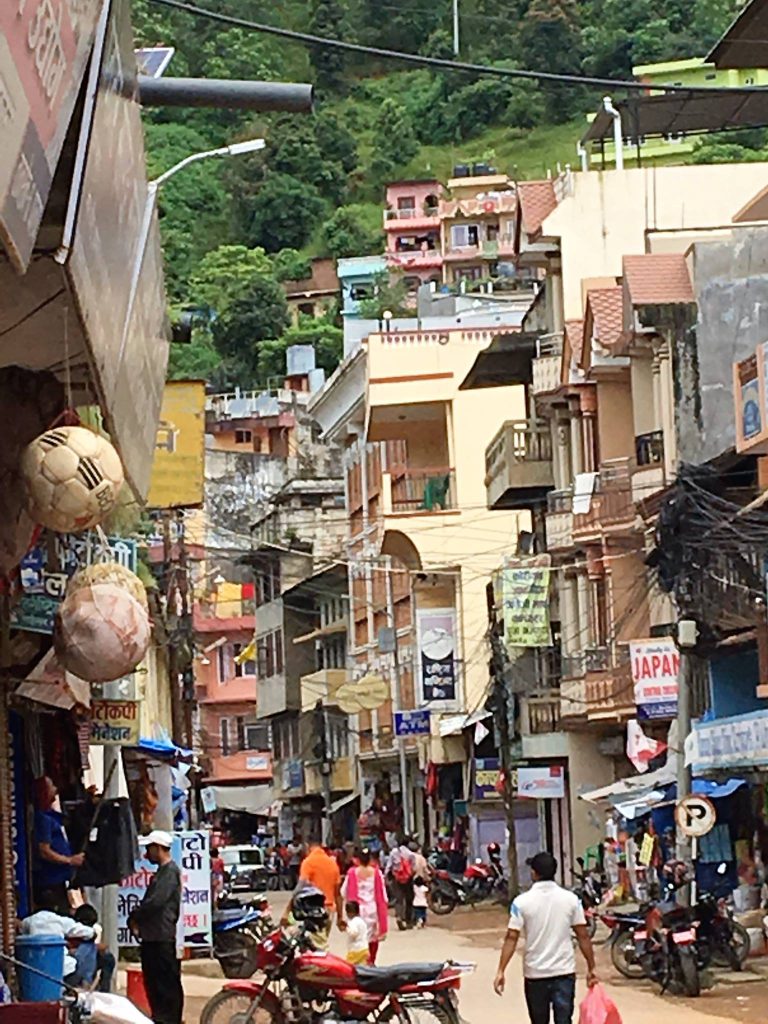

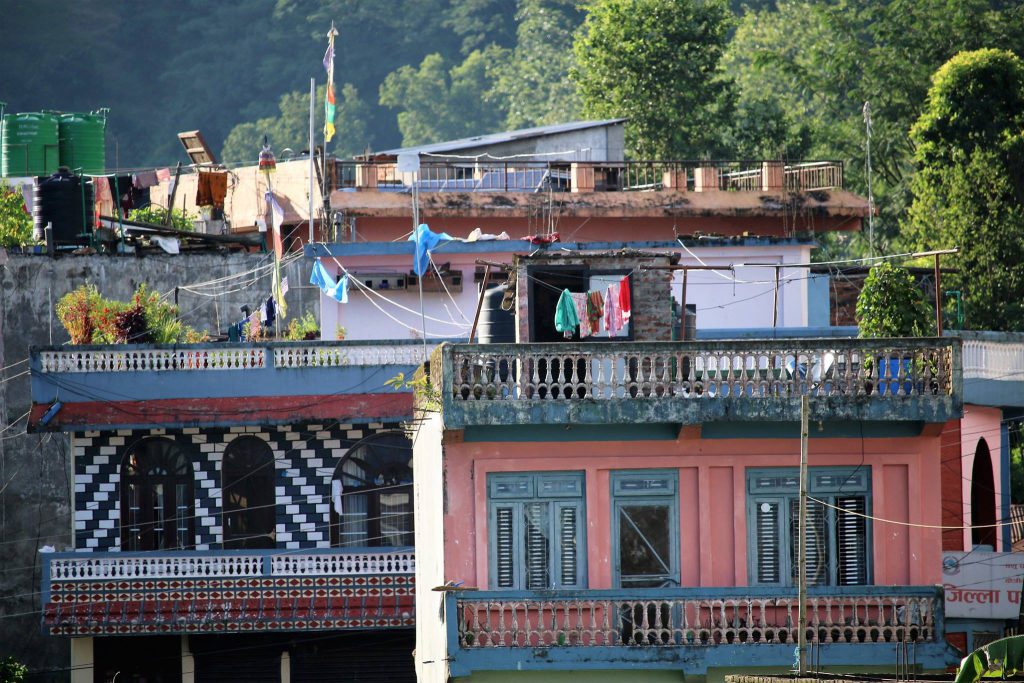

Trekking Across Nepal

Rwanda: Akagera National Park and Kigali